Sulfide Mining is Destructive and Dangerous

Many minerals of economic interest (such as nickel, copper, gold and cobalt) are found in high sulfide ores. The minerals in these ores are bonded to sulfur, forming sulfide minerals. The amount of sulfur in these ores can range as high as 70% (see talonmetals.com/talon-metals-feasibility-study-drilling-shows-potential-lateral-extention-of-high-grade-nickel-copper-mineralization-beyond-the-southernmost-tip-of-the-tamarack-resource-area/. However, the usable mineral content and associated sulfur is generally much lower. In the case of the proposed Tamarack/Talon/Rio Tinto underground mine in Minnesota, nickel comprises only 1.73% of the ore on average (talonmetals.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Final_NI43101_Report_Talon_TamarackN_20221102.pdf. Other high sulfide nickel and copper mine proposals in Minnesota claim mineral content even lower, often less than 1%. Nevertheless, the sulfur content of these ores may be 5-10 times higher than the mineral of interest. As such, high sulfide mining creates a very large amount of waste sulfur which is often discarded into the environment with toxic affects. Alternatively, iron ore deposits in the midwest have very little sulfur.

Toxic Consequences of High Sulfide Mining

Sulfur waste from high sulfide mining operations as well as exploratory bore hole cuttings have at least 3 toxic consequences for the environment and the general population.

- Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) - When sulfide mining waste is exposed to air and moisture, a chemical reaction occurs over time that generates sulfuric acid which migrates into the surrounding environment and, through leaching, releases heavy metals present in the waste rock, pit walls, and tailings basins of mining operations. The sulfuric acid along with dissolved heavy metals released onto the land will seep into the aquifers below and then into streams and lakes at levels that are toxic to fish and other aquatic life. This process can often take 20 years or more to unfold and as such, becomes a ticking time bomb in high sulfide mining areas. The close proximity of sulfide mines to valued water bodies such as lakes and rivers of the Mississippi watershed intensifies the magnitude of this issue. All of the water bodies in the Tamarack Minnesota area are linked by multiple aquifers.

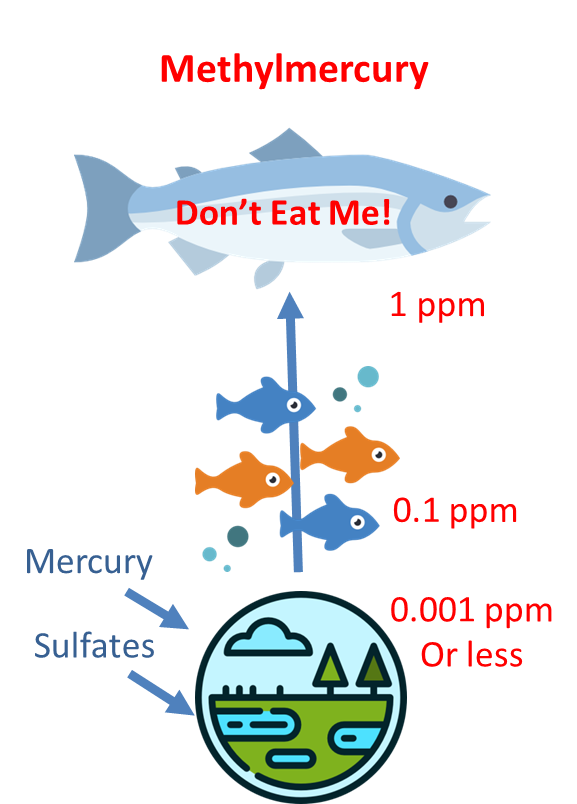

- Sulfur reducing bacteria convert free mercury in the environment to methyl-mercury, a potent neurotoxin which can accumulate in fish creating fish consumption limits. Consumption of methy-mercury contaminated fish can cause serious health problems.

- Wild rice is very sensitive to sulfate levels and require an environment where sulfate levels are less than 10ppm – thus even relatively low levels of sulfates in wild rice areas can decimate wild rice crops. Wild rice is very difficult to reintroduce once its gone.

To make matters worse, the sulfide mining industry has a poor history of stewardship, integrity and accountability. To date, no sulfide mine in a water rich area has been able to operate without causing some form of pollution in the surrounding environment (see references below). Talon Metals (who plans to mine in Tamarack, Minnesota) points to the Flambeau Mine in Wisconsin and the Michigan Eagle Mine as model cases of environmental stewardship; however, both sites have very serious environmental issues as noted later.

Acid Mine Drainage - Sulfide Mines Lead To Contaminated Water

Many organizations have noted that anytime a sulfide mine has been built in a water rich area, the water has been contaminated. Of course, new mines open over time so no single reference can ever be "up to date" in support of this statement. Nevertheless, we can show that no mine has been found to not contaminate the local water based environment, particularly in wetland areas.

- It is interesting to note that, from the EPA superfund website, 42 past mines in the US are now EPA Superfund sites. The number was much larger in the past. (see www.epa.gov/superfund/national-priorities-list-npl-sites-state. Why are we using taxpayer dollars to pay for the sins of the (often foreign) mining companies. We need stronger mining laws to prevent polution in the first place and stop spending our tax dollars to support (often) foreign mining conglomerates.

- The research paper available at earthworks.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Porphyry_Copper_Mines_Track_Record_8-2012.pdf was reviewed by Dave Chambers Ph. D., and the Center for Science in Public Participation (CSP2). The report considered state and federal documents and a federal database for fourteen copper porphyry (igneous rock) mines operating in the U.S. with respect to three failure modes: pipeline spills or other accidental releases, tailings spills or tailings impoundment failures, and failure to capture and treat mine seepage. The mines were chosen based on an operating record of more than five years and represents 89% of U.S. copper production in 2010. The research shows that all of the mines experienced at least one failure, with most mines experiencing multiple failures and that copper porphyry mines are often associated with water pollution associated with acid mine drainage, metals leaching and/or accidental releases of toxic materials. These failures resulted in a variety of environmental impacts, such as contamination of drinking water aquifers, contamination and loss of fish and wildlife and their habitat, and risks to public health. In some cases, water quality impacts are so severe that acid mine drainage will generate water pollution in perpetuity. Many of the currently operating copper porphyry mines are located in the arid southwest, where precipitation is limited, and communication between surface and groundwater resources is limited. While beyond the scope of the analysis in this report, more significant impacts could be expected at mines in wetter climates, with abundant surface water and shallow groundwater.

- Additionally, research (Kuipers, J.R., Maest, A.S., MacHardy, K.A., and Lawson, G. 2006. Comparison of Predicted and Actual Water Quality at Hardrock Mines: The reliability of predictions in Environmental Impact Statements (tamarackwateralliance.org/docs/KuipersMaest2006_EISComparisonsReport.pdf) shows that mines with high acid generating potential and in close proximity to surface and groundwater are at highest risk for water quality impacts. This report studied 25 operating hard rock mines and their EISs. All predicted compliance with water quality standard within their EISs however pollution from 85% of mines near surface water and 93% of mines near ground water exceeded water quality standards. In addition, 89% had inaccurately predicted that they would not create AMD.

Sulfate Reducing Bacteria Produces Methylmercury

Atmospheric mercury (Hg) is the dominant source of Hg in northern Minnesota. Taconite plants, are the largest industrial source of mercury pollution in Minnesota, have vented the toxic metal for years into the air without enforced limits. (startribune.com/epa-rule-targets-taconite-industry-mercury-polluter-minnesota-coal-regulation-earthjustice-tribe/600274349). Coal-fired power plants are another significant source of mercury. Atmospherically derived Hg must be methylated prior to accumulating in fish and sulfate-reducing bacteria are the primary methylators of Hg in the environment. Thus sulfur plus mercury creates methylmercury which is a potent neurotoxin. Methylmercury is fat soluble and thus can “bio-magnify” in the food chain (in fatty tissues), primarily in fish and shellfish.

See list of Minnesota Impaired Waters: https://www.pca.state.mn.us/air-water-land-climate/minnesotas-impaired-waters-list

Minnesota Lake Finder for more detail:

https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/lakefind/lake.html?id=01002300

Fish consumption guidance can be found here:

https://www.dnr.state.mn.us/lakefind/fca/report.html?downum=01002300

Methylmercury can cause a wide range of health effects, including:

Methylmercury can cause a wide range of health effects, including:

- Neurological damage (e.g., tremors, seizures, memory loss)

- Kidney damage

- Cardiovascular problems

- Developmental problems in children (e.g., brain damage, motor coordination difficulties)

The "Mercury in Newborns in the Lake Superior Basin" study showed that ten percent of tested newborns in the Minnesota arrowhead had concentrations of Mercury above the reference dose. This is in contrast to a 3% rate in Wisconsin and 0% of Michigan samples were above the U.S. EPA dose limit. It is likely that taconite mine operations and associated release of sulfur on the iron range has created increased methyl-mercury load in local fish. Indeed, babies born during the summer months were more likely to have an elevated mercury level suggesting that increased consumption of locally caught fish during the warm months is an important source of pregnant women's mercury exposure in this region (www.health.state.mn.us/communities/environment/fish/techinfo/newbornhglsp.html).

Karen Wetterhahn, a chemistry professor at Dartmouth College, died from mercury poisoning in 1997 due to accidental exposure to methylmercury. A few drops of the highly toxic compound seeped through her latex gloves. This led to her death about a year later from mercury poisoning en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karen_Wetterhahn.

Sulfur historically comes from coal plants (e.g. Acid Rain), and to a lesser extent fertilizers and some soaps. However, high sulfide mining operations and associated sulfur waste will greatly intensify this issue.

Additional References:

- www.fs.usda.gov/nrs/pubs/jrnl/2006/nc_2006_jeremiason_001.pdf

- www.pca.state.mn.us/pollutants-and-contaminants/mercury

- pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3514465/

- www.ucsfhealth.org/medical-tests/methylmercury-poisoning

High Sulfide Mines Can Generate High levels of Toxic Dust and Gases Vented into the Atmosphere

Mining activities such as shoveling, bulldozing, and blasting, crushing, grinding, and screening rock, soil, and other materials can result in dust (PM10) air pollution. Vented dust from high sulfide mine operations (PM2.5 and PM10) will have high sulfate concentrations and can travel 30 miles. (www.clarity.io/blog/pm10-air-pollution-from-mining-activities-monitoring-dust-for-mining-operations ). Sulfate particulate matter settles on the land, washed into rivers and wetlands over many years resulting in sulfate based environmental damage.

In addition, blasting associated with hard rock mining generates large amounts of toxic gases that are vented into the atmosphere. Blasting with ammonium-nitrate fuel-oil (ANFO) explosives creates high concentrations of NOx gases. Large localized plumes from blasting can exhibit high NOx concentration (500 ppm) exceeding up to 3000 times international standards. Blasting of high sulfide ore also creates toxic H2S and SO2. Both SO2 and NOx produce acid when exposed to water and air. These gases can travel hundreds miles in the air and create acid rain (primary cause for coal based acid rain).

Additional References:

- www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1352231017305113

- pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10727359/

- uat-oneminewebsite.azurewebsites.net/documents/ri-2863-explosibility-of-sulphide-dusts-in-metal-mines

- www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-08/documents/2005report.pdf

More Examples of Acid Mine Drainage (AMD)

Acid runoff from the Summitville Mine in Colorado killed all biological life in a 17-mile stretch of the Alamosa River. The site was designated a federal Superfund site, and the EPA has spent over $210 million on clean-up.

Zortman Landusky mine in north central Montana filed for bankruptcy in 1998 leaving the state of Montana with the liability for $33 million in long-term water treatment and reclamation costs.

Torch Lake in Houghton County, MI is a superfund site. Copper mining activities in the area from the 1890s until 1969 produced mill tailings that contaminated lake sediments and the shoreline. Fish were found with cancerous tumors and high levels of copper, arsenic, mercury and PCBs. Remediation efforts started in 1998 and continued through 2006 – EPA updated the cleanup plan in Nov 2024. Note here that environmental damage may not be recognized until nearly 20-30 years after mine closure. It often takes a quite a bit time for the toxic materials to seep into sensitive areas and for the chemical reactions noted to occur.

MPCA (Minnesota Polution Control Agency) recently announced that Birch Lake near the Boundary Waters has excessive sulfate in its water (impaired). The Dunka taconite mine (closed in 1991) waste rock piles, which are 80–100 feet high and extend for almost a mile, have been leaching metals into the streams and wetlands that flow into Birch Lake. Several lakes and rivers upstream of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness are contaminated with sulfate, which causes more mercury in fish and kills manoomin (wild rice), according to the MPCA and several citizen-led sampling efforts. Waters downstream of past and present iron mines exceed standards for sulfate levels designed to protect the environment.

The Northern Lakes Scientific Advisory Panel, or NLSAP, monitors (sulfate based) water pollution in Voyageurs Park and the BWCA in cooperation with the MPCA and have measured high levels of sulfate. See the video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZW8p640wNno for more detail.

Thus we have not found a high sulfide Nickel / Copper mine in wetland areas that has not polluted. Some people raise the question as to whether the Wisconsin Flambeau mine or Michigan Eagle mine have polluted the local environment or not.

Flambeau Mine Wisconsin

The Flambeau Mine is sometimes presented as an example of a clean sulfide mine. This mine was a very small open pit mine (32 acre pit) on a 161 acre mine site which operated for only for 4 years. Despite the short exposure to sulfide mine contamination, significant issues exist.

Here we note that the federal district court found that the mine discharged copper contamination at levels exceeding state standards ( www.casemine.com/judgement/us/5914f59aadd7b0493498b3f0). However, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals then ruled that this case could not proceed further, since Flambeau was entitled to a "permit shield" because it had no notice its state permit wasn’t valid so was entitled to rely on that permit. In other words, the State of Wisconsin approved the contamination. And of course, the court did rule that the mine did release pollution.

Although the state of Wisconsin considers the Flambeau Mine a successful reclamation, significant contamination of the surrounding area has been documented. Specifically, surface water runoff from the mine site does not meet Wisconsin surface water quality standards. Runoff is polluting a stream which flows into the Flambeau River. Multiple water samples between 2004 and 2008 show significantly elevated levels of copper, exceeding standards. Studies show that the stream is almost devoid of life, including vegetation and fish. Researchers believe this is because of the high metal levels. At one location, the copper level was approximately 10 times the acute water quality standard, and the zinc level is approximately twice the acute water quality standard. Copper and Zinc combined impact on aquatic organisms is greater than that of either by itself. (wisconsinrivers.org/flambeau-mine-closure-statement/)

One of the difficulties facing the metals-mining industry has been its inability to predict the quality of the water mining will leave behind. The Flambeau mine is a case in point. The mine permit application predicted the level of manganese in water entering the Flambeau River would be a quarter of what it actually is (between 2,000 and 2,500 micrograms per liter). The Environmental Impact Statement painted an even rosier picture, assuring the public that the highest level of manganese within the backfilled mine pit would be 400 micrograms per liter; the actual level is as high as 40,000 micrograms per liter in one area. The groundwater standard for manganese is 300 micrograms per liter, set to protect drinking water.

According to Flambeau’s permit application, manganese levels are likely to remain high for more than 4,000 years. Wisconsin (and Minnesota) law allows mining companies to pollute the groundwater at mine sites, and Flambeau’s polluted groundwater does not violate the law. But 4,000 years is a long time, and we cannot know how conditions will change over that kind of time frame. This is pollution that has been bequeathed to future generations and most likely to a future civilization that does not have access to our records. Is this really what we want to emulate in Minnesota?

In addition, consider:

- deertailscientific.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/foth-flambeau_dts_2024_.pdf

- deertailscientific.files.wordpress.com/2021/02/moran-flambeau-rept-key-findings_u.pdf

- deertailscientific.files.wordpress.com/2021/01/2020flambeausnapshot_dts.pdf

- deertailscientific.wordpress.com/flambeau-snapshot/

- flambeaumineexposed.wordpress.com/model-mine-myth/

This independent work was done by experienced PhD scientists and demonstrate significant pollution from the Flambeau Mine. Indeed, the Flambeau Mine Corporation does not deny any of this nor do they produce additional results to argue an opposite claim.

The issue is that the state of Wisconsin failed to properly baseline the area and did not implement monitoring at points susceptible to sulfide contamination. As such the state of Wisconsin refuses to acknowledge that the pollution was caused by the mine but claims that these events "could have" been present prior to mining. Nevertheless, local observers beg to differ. A significant failure by the state DNR DOES NOT mean the Flambeau Mine is clean!

Eagle Mine Michigan

The Eagle Mine is still in operation and historically we see that AMD often does not manifest for a number of years after closure.

However, even now given just a few years of operation, we see significant anomalies in monitoring when looking at the official mine report to the Michigan Government. Consider the document: www.eaglemine.com/_files/ugd/c6167e_ffef87e367c44b98a35291842533f161.pdf.

Eagle Mine Anomalies Report listed over 20 monitoring situations that show levels of pollution and water chemistry changes outside the planned benchmark range. For example, QAL023B monitoring point showed the water level was 5.6 feet below the calculated minimum baseline level. Mine attributed this drop in water levels to two main sources; pumping of the mine services well and groundwater infiltration into the mine. This drop in water levels is then due to an average pumping requirement of 80,000 to 150,000 gallons a day from the mine and service wells. If 5.6’ drop is seen at these pumping rates, what happens when Talon estimates over 2,300,000 gallons pumped per day in Tamarack?

Other examples of Eagle Mine Anomalies Reported include:

- Many monitoring points showed sulfate levels 1500 times higher than the MN standard for sulfates in wild rice environments

- Eagle mine reported a decrease in bird and fish populations

- Location QAL024A had benchmark deviations in bicarbonate alkalinity, chloride, nitrate, and sodium.

- Nitrates were detected above the benchmark during all four sampling quarters in 2022 at monitoring wells QAL060A and QAL061A

- Location QAL062A had results for pH, alkalinity bicarbonate, chloride, nitrate, and sodium that were outside calculated benchmarks for each sampling event in 2022

- Bicarbonate alkalinity, chloride, nitrate, and sodium were above benchmark levels at QAL063A

- QAL066D had results for iron, bicarbonate alkalinity, and sodium that were above benchmark levels for all the sampling events in 2022

- Location QAL067A had benchmark deviations for chloride, sodium, bicarbonate alkalinity, sulfate, and nitrate for all 2022 sampling events and Calcium, magnesium, potassium, and hardness were also above established benchmarks for at least two consecutive Q2 annual sampling events

- .... And the list goes on …

Eagle Mine does a very poor job at managing dust – a possible cause of the water contamination demonstrated in the above referenced Eagle Mine Exception report. After including an air filtration system in its original permit, Eagle sought to have it removed in 2013, which the MDEQ approved, blowing a plume of unfiltered mine emissions out over the Salmon Trout River and the Yellow Dog Plains. No stack monitoring is taking place, and the emissions have not been measured since September 2014, before the mine was in full operation. (Source: Mining Action Group savethewildup.org/about/eagle-mine-facts/ and savethewildup.org/2013/03/air-filtration-necessary-on-eagle-mine-air-stack-to-keep-air-clean/).

The Eagle Mine TDRSA (Temporary Development Rock Storage Area) is lined with both a primary and secondary lining. A leak detection system is installed between the liners to monitor primary lining integrity. A total of approximately 55 gallons of water was purged from the leak detection sump in 2020, a larger volume than 2019. Thus we see that the lining system does leak after only a few years of operation. The leak levels are currently very small at this point but as noted in the document, increasing slightly over time.

Indeed one cannot find a Sulfide Mine that is not damaging in a wet environment.

Sulfide Mining Perpetrates Environmental Injustice

The existence of a sulfide mine in an area harms communities. The inevitable contamination of local water will negatively impact the wild rice beds that are currently used to sustain many in the community. In addition, fish and wildlife are negatively impacted.

Contamination from the proposed Talon Tamarack mine from wind blown dust, water contamination will have a long lasting impact on the local environment.

Property values drop as nobody wants to buy property that is or will certainly be contaminated in the future. Who wants property next to a toxic mine?

Sulfide Mining Threatens Tribal Wild Rice Resources

Minnesota ranks #1 in the United States for wild rice production, both naturally grown and cultivated Wild rice is very sensitive to sulfide contamination.

Anishinaabe seasonally harvest tens of thousands of acres of wild rice in Northeastern Minnesota’s undisturbed watersheds Manoomin is sacred to their way of life.

Pristine water quality must be maintained for wild rice to germinate, grow, and survive. Sulfates bound in glacial/bedrock geology are released when the water is disturbed due to mining, endangering wild rice fields. Many lakes and streams around the Great Lakes have already lost their wild rice. Wild rice is hard to restore once it is gone.

Minnesota’s wild rice sulfate standard limits sulfates to 10 parts per million (ppm or mgL) in wild rice waters. However, many politicians are bent on weakening this standard in support of mining - destroying a national treasure.

Does the US Need Minnesota Nickel?

Based on the US Geological Survey (USGS) 2025 report (pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2025/mcs2025-nickel.pdf), the proposed Tamarack Mine will make NO difference in the global supply of nickel but only serve to increase profits for Rio Tinto, a large foreign mining company. The USGS report shows that currently, only 0.22% of the world’s supply of nickel comes from the US (primarily from Michigan Eagle Mine). In addition, the same report notes that the majority of nickel used in the US is from recycled sources. Mining is fundamentally not a sustainable activity. Minerals don't grow on trees. Recycling is the only long term answer.

In fact, the US only possesses 0.24% of the worldwide reserves of nickel (in Michigan and Tamarack). Right now, the Eagle mine is shipping their nickel to Canada for processing where it sold on the global markets. It is likely that Talon will do the same as nickel is engineered out of EV batteries (see tamarackwateralliance.org/evs.html). Instead of shipping this nickel onto global markets / China, should we not save our meager reserves for the future? Are the profits for Rio Tinto worth the destructive impacts of sulfide mining?

The USGS report also notes that the majoriy of nickel reserves are in laterite ores (nickel with iron and aluminum oxides) not high sulfide ores. Why are we mining toxic high sulfide ores when non-sulfur producing options exist? (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lateritic_nickel_ore_deposits)

High Sulfide Mining is Much Different Than Taconite Mining

Taconite (Iron) nined on the range is low grade ore (20-30% iron) and is bound in silica minerals (SiO2 like quartz, feldspar … asbestos, …). Silicates are the most common rock-forming minerals on earth and make up a large portion of Earth's crust.

Alternatively, nickel from underground mines (like the Tamarack Talon mine) is generally in the range of 1.5-2% nickel. Open pit mines can have very low grades from 0.08% upward toward 0.5%. In the Midwest, the nickel and copper ore from high sulfide mines are bound with a great deal of sulfur, often from 30-70% sulfur. As such, a high sulfide mine might have more than 10 times as much sulfur as the mineral being mined. This sulfur is discarded as waste (and lots of it) providing a source for a great deal of environmental damage.

Additional References

For more information on the dangers of sulfide mining:

Sierra Club (www.sierraclub.org/minnesota/mining/sulfide-mining)

Mining Action Group (savethewildup.org/about/sulfide-mining-101/)

Mine EPA Superfund Sites - use your browser to search on keyword "mine" www.epa.gov/superfund/national-priorities-list-npl-sites-state

Earthworks - Copper Sulfide Mining (earthworks.org/issues/copper_sulfide_mining/)

U.S. Copper Porphyry Mines Report providing 14 detailed case studies on mining polution.

(earthworks.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Porphyry_Copper_Mines_Track_Record_8-2012.pdf)

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23625128/

Sahoo, P. K., Kim, K., Equeenuddin, S. M., & Powell, M. A. (2013). Current approaches for mitigating acid mine drainage. Reviews of environmental contamination and toxicology, 226, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6898-1_1

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30476429/

Onello, E., Allert, D., Bauer, S., Ipsen, J., Saracino, M., Wegerson, K., Wendland, D., & Pearson, J. (2016). Sulfide Mining and Human Health in Minnesota. Minnesota medicine, 99(8), 51–55.

Official 2020 mine report to the Michigan Government ( www.michigan.gov/-/media/Project/Websites/egle/Documents/Reports/OGMD/2020-ogmd-eagle-mine-annual-report.PDF.